Workers’ skills and occupations play a major part in economic development. In fact, the formation, composition and allocation of ‘human capital’ largely explain differences in income between countries around the world. The availability and productivity of high-skilled jobs also matter – education alone is not the route to prosperity. Workers must also be given the labour market opportunities to deploy high-productivity skills in the right roles.

The question of why countries differ so dramatically in their income levels is one of the most persistent puzzles in development economics. In a new working paper – written with Charles Gottlieb (Aix-Marseille School of Economics and University of Geneva) and Jan Grobovšek (Universities ofEdinburgh and Ljubljana) – we examine how workers with different skills sort into various jobs/occupations across 50 countries. Our study reveals that human capital (i.e., people’s skills) plays a much larger role than previously understood – accounting for roughly half of cross-country GDP differences.

Traditional development accounting has long struggled to pin down the scale of the relationship between human capital and inter-country income gaps. Early research treated all workers as ‘perfect substitutes’ (i.e., the theory assumes people are interchangeable) and found that human capital explained little of the variation between different economies. Later work then allowed for ‘complementarity’ between skilled and unskilled workers (i.e., the idea that people can affect one other’s productivity) but faced challenges distinguishing between human capital quality and ‘skill-biased’ technology. So, despite extensive analysis, the picture remained murky.

Our latest research breaks new ground by modeling how workers of different education and experience levels sort across eight broad occupational categories based on comparative advantage. The key innovation is recognising that the value of human capital depends critically on the job-specific tasks workers end up performing. Skilled workers can only contribute their full potential when channeled toward activities where they have strong comparative advantage (i.e., where they are better/more productive than their unskilled counterparts).

Using micro data spanning the entire development spectrum, we construct a general equilibrium model where occupational assignment depends on worker productivity, human capital quality, job-specific technology, and institutional context. This framework allows us to separate human capital quality from technological factors – a major methodological advance.

Richer countries excel in complex occupations

Our findings paint a clear picture of how economic development progresses. Rich countries have particularly high productivity in more complex, white-collar occupations, with productivity growth appearing biased toward professional, managerial and technical roles. This ‘bias’ explains why 59% of workers in the richest quintile of countries work in white-collar occupations, compared with just 16% in the poorest quintile.

Our research also reveals that when conditioning on human capital the propensity to work in white-collar jobs is only slightly higher in rich countries. This suggests the dramatic differences in occupational structure primarily reflect variation in human capital composition rather than differing access to complex jobs.

Wage patterns are equally telling. Both the white-collar wage premium and the high-skilled wage premium decrease as GDPrises, even after controlling for human capital composition. In the poorest countries, white-collar workers earn 151% more than blue-collar workers, compared with just 49% more in the richest countries. It pays to have extremely scarce skills, after all.

Human capital quality varies across countries

A major contribution of our new work is to document systematic patterns in human capital quality across the development spectrum. We find that human capital quality for all but the least-skilled workers is, by and large, higher in richer countries. This advantage is particularly pronounced for secondary-educated workers and older, more experienced workers – consistent with evidence that the ‘returns to experience’ are higher in developed economies.

Crucially, these quality differences vary from job to job, suggesting that the value of education and experience depends on the specific tasks workers perform. This occupational dimension of human capital quality has been largely overlooked in previous research but appears essential for understanding development patterns.

Quantifying the impact of human capital

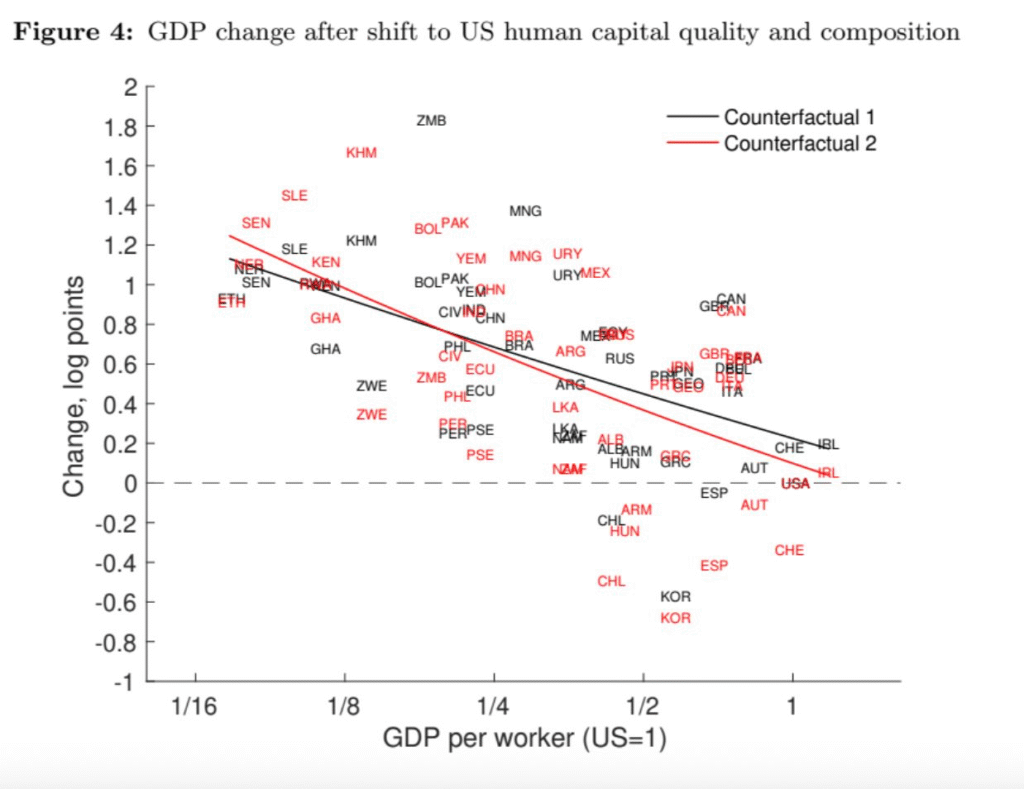

Our study’s counterfactual experiments yield striking results. For the poorest quintile of countries, a shift to US levels of human capital would double non-agricultural GDP and the white-collar employment rate, while decreasing the wages of white-collar workers relative to blue-collar workers by 30%.

Perhaps most significantly, the composition and quality of human capital explain half of the cross-country non-agricultural GDP per worker gap relative to the United States. This finding substantially exceeds estimates from traditional research approaches and re-positions human capital as the dominant factor in development accounting.

The decomposition reveals that education matters more than age structure, though both contribute. About 80 percentage points of the GDP gain for the poorest countries comes from shifting educational composition, with demographics accounting for a smaller but meaningful portion.

Occupational distortions matter, but less than expected

Occupational distortions – wedges or barriers precluding some workers from maximizing the productivity of their skills – across occupations are natural candidates for the lack of productivity in poor countries. But while we find that these distortions are more pronounced in poor countries and systematically discourage white-collar employment, their quantitative impact on aggregate output is surprisingly modest. They depress white-collar employment and contribute to a higher wage premium yet have a minor effect on output.

This result challenges some recent work emphasising misallocation as a primary driver of development differences. While distortions clearly exist and affect the sorting of workers and jobs, their overall consequences appear limited compared with fundamental differences in skills and productivity.

Implications for development policy and research

Our findings carry important implications for both policy and research. For policymakers, the results underscore human capital investment as a central component within development strategy, but with important nuances. The occupational dimension suggests that not all education or experience are created equal – their worth depends on the economy’s ability to productively employ skilled workers in complex jobs.

The research also highlights ‘complementarities’ between human capital and occupational productivity. Countries cannot simply educate their way to prosperity without simultaneously developing the institutional and technological capacity to employ skilled workers effectively. This may help explain why some countries with rapidly expanding education systems have not seen commensurate growth benefits.

For researchers, this work demonstrates the value of detailed occupational analysis in development accounting. The idea that the contribution of human capital depends critically on occupational sorting suggests that aggregate approaches may systematically underestimate its importance. Future research should explore how policies affect both human capital accumulation and the occupational structure that determines its use.

This research significantly advances our understanding of the development process. Human capital is more important than previously recognised, and the occupational structure of an economy plays a key role in determining how that people’s skills contribute to growth. Both our framework and findings should prove useful for academic research and policy discussions about the future of development strategy.