A new index measures how much richer countries would be if women and men worked, earned, and were employed on equal terms.

Across the world, married women spend around 2.5 times more hours doing household chores than married men — every single week. Women are also less likely to have a formal job contract that pays wages, instead working under informal, unpaid arrangements. Moreover, women earn less and participate less in the labour force.

What if women faced a level playing field? If the burden of household chores was shared equally, just as many women had formal contracts as men, and wages were the same for doing the same work — what would that do to the economy at large?

In a new paper, researchers at the University of Geneva, Yale University and the World Bank create the Global Gender Distortions Index (GGDI), a new indicator that answers precisely this question. Leveraging the rich micro-data from Work-in-Data’s Harmonized World Labor Force Survey (HWLFS), the paper calculates the GGDI for 50 countries. Grounded in economic theory, the index outputs a single number that shows what would happen to economies if their labour markets were gender blind. The answer? A lot.

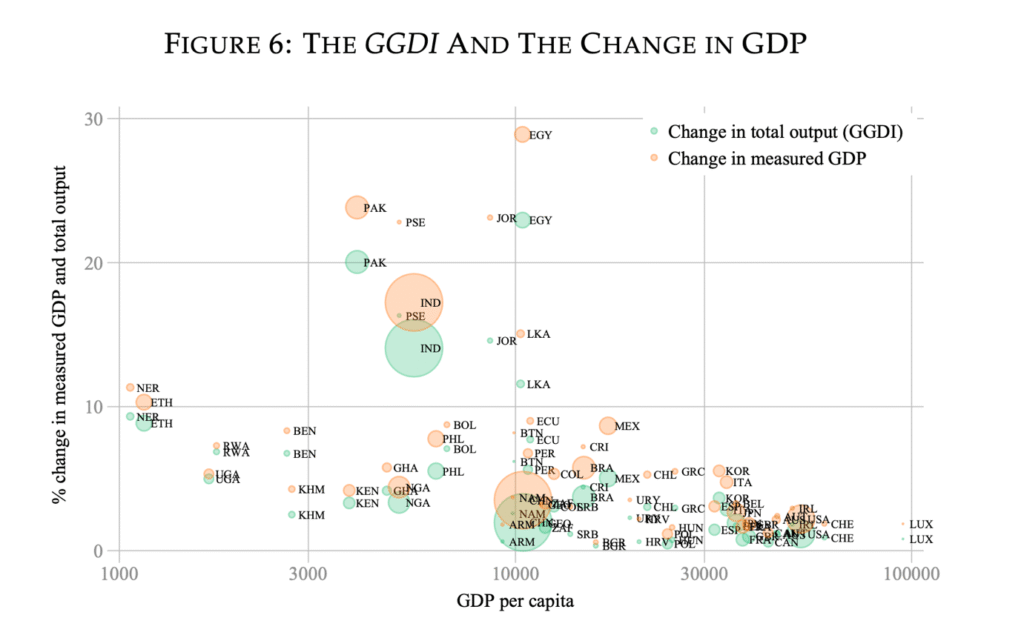

When we give women equivalent outcomes to men, economic activity increases by up to 20 percent, yearly. Under a gender blind scenario, Egypt and India’s GDP could be 28 percent and 15 percent higher, respectively. Even Switzerland and Luxembourg, two of the world’s richest countries, would see two percentage points added to their economic output.

Note: GGDI measures the increase in total economic activity (including home production) due to the removal of labor demand and labor supply gender distortions. Measured GDP is the increase in GDP following the removal of labor demand and labor supply gender distortions.

How can countries capture these gains? That requires understanding why women have worse outcomes on the labour market than men. The proposed methodology can quantify the role of demand and supply factors that shape women’s labor market outcomes. Labour demand factors appear on the firm side — for example, companies may discriminate by paying women less or offering flatter career ladders. Labour supply factors are forces that constrain the individual — for example, institutions or deeply entrenched gender norms.

The paper finds that in most countries, labour demand factors are a more potent barrier to women’s participation in the labour market. That’s good news for policymakers — demand factors are much more readily influenced than deeply held societal norms that put a brake on women’s supply of labour. Through anti-discrimination laws, regulating recruitment practices, or forcing better job amenities for women, policymakers can mitigate some of the obstacles that women face in accessing quality jobs and start to capture the macroeconomic benefits of greater female employment.

The GGDI’s simplicity makes it a powerful tool to measure and communicate gender disparities — and to push policymakers to routinely factor gender into macroeconomic decision-making. But the message goes beyond gender: unequal opportunities between men and women reflect a broader misallocation of talent. When half of the population faces barriers to using their skills fully, the economy runs below potential. The GGDI helps reveal how much human capital remains untapped. Its framework is also flexible: in high-income countries, it can be adapted to study unequal access to high-skill occupations such as law, medicine, or technology; in lower-income settings, it can capture gaps in job formality and pay. Ultimately, the index reminds us that economies grow stronger when everyone can contribute to their full potential.

You can find the paper here and the matlab codes to replicate and expand the index. The authors would be glad to engage with policy makers willing to adapt the index to their policy questions.