Large firms are not getting the skilled workers that they need, holding back firm growth and thereby entire countries.

Six billion people living in the world’s 108 middle-income countries face an uphill battle to attain high-income status over the next few decades. The “middle-income trap” made that transition hard enough, without the rising debt, aging populations and growing protectionism that increasingly burden policymakers. Using data from Work-in-Data, a new paper identifies a previously understudied cause of this “trap”: the interplay between low skill levels and firm size. The findings offer policymakers a fresh channel through which to build better growth strategies.

The “middle-income trap” is an economic phenomenon where countries, after reaching middle-income status1, experience a significant slowdown in growth, preventing them from transitioning to a high-income country. Since 1990, just 34 middle-income countries have managed to reach high-income status — the majority of which through EU integration or newly discovered oil deposits.2

A key cause of the middle-income trap is weak firm growth. Research has shown that large firms are better at adopting new technologies and innovating, leading to higher productivity and economic growth. Yet firms in poorer countries often struggle to grow. One reason is institutional weakness, such as legal uncertainty, which makes entrepreneurs wary of the rule of law and inclined to stay small and out of sight.3 Similarly, many firms in developing countries are reluctant to delegate tasks to outsiders. In India, for example, firm size is strongly predicted by the number of sons in a family, highlighting a deeply rooted lack of trust that limits expansion.4

A previously underexplored reason for why firms remain small is skill level. Managerial delegation implies not only trust, but skill. A growing firm requires expertise in accounting, human resources, marketing, and the skill of delegation itself — and cannot easily hire a low-skilled person to do those jobs.

Until now, it was impossible to observe how skill level varies across firm size globally, since there were only separate datasets tracking firm size and education. Work-in-Data’s HWLFS dataset harmonises thousands of labour force surveys from 54 countries, which ask individuals both their education level and the size of the company where they work. That allows us to simultaneously observe how skilled someone is and the size of the company where they work.

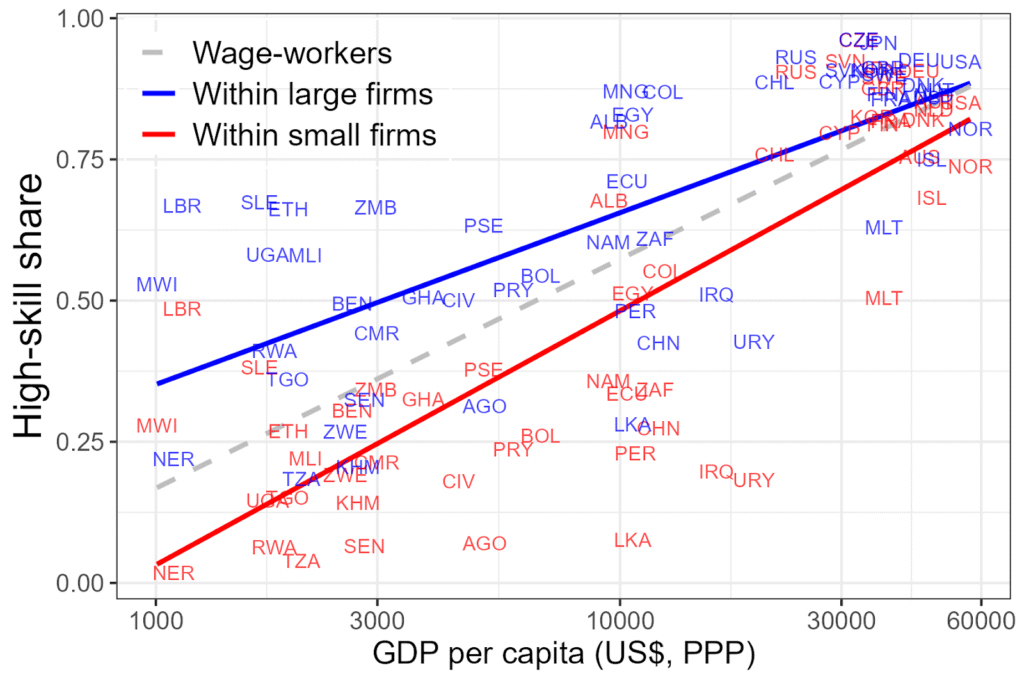

Using HWLFS, the study reveals that a lack of talent hinders poor countries by holding back large firms. The graph below shows the skill level of employees in big and small companies across 54 countries. Large firms always employ more highly skilled people than small firms, but the difference narrows drastically as a country gets richer. Take the United States: about 90 percent of employees in big firms are highly skilled, compared to about 80 percent in small firms, a 10 percent difference. In Malawi, one of the world’s poorest nations, 53 percent of a large firm’s employees are highly skilled compared to just 26 percent in small firms.

Small firms have fewer than 10 employees. Large firms have 10 or more employees. We define “high skills” as more than 9 years of education, which typically corresponds to education beyond lower secondary school. We choose this threshold to ensure comparability, especially since many low-income countries have very limited numbers of college-educated workers.

On average, the difference in skill intensity between large and small firms is 24 percentage points in poor countries, but just five percent in rich countries. The wide gap demonstrates the necessity for skilled workers in large firms, regardless of how educated a country is.

When talent is rare and expensive — in a country like Malawi — it makes it harder for large firms to expand. But these are the firms expected to drive growth and innovation in poorer countries, where the world of work is dominated by small and inefficient firms. To support large firms and reap the many macro benefits they bring, policy makers must invest in the human capital of their populations. Schooling and education matters not only for worker productivity, but is also an important contributor to firm growth.

You can find the new paper by Charles Gottlieb, Markus Poschke and Michael Tueting here.

References

- Defined by the World Bank as an income per capita of between US$1,136 and US$13,845.

- “The Middle-Income Trap”, World Development Report 2024, World Bank, available here.

- See Restuccia, D., and R. Rogerson (2008) ‘Policy Distortions and Aggregate Productivity with Heterogeneous Plants,’ Review of Economic Dynamics 11(4), p707-720; Hsieh, C., and P. Klenow (2009) ‘Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India,’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4), p1403-1448.

- Bloom, N., B. Eifert, D. McKenzie, A. Mahajan, and J. Roberts (2013) ‘Does Management Matter: Evidence from India,’ Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1), p1–51.